The House with a Tower: Tragedy, Mystery, and Art at Goyki 3

Kamil Antoniuk reveals the haunting history of Sopot’s most intriguing villa, where a family’s tragic past meets a vibrant cultural future

By Ged Brown, Founder and CEO of Low Season Traveller

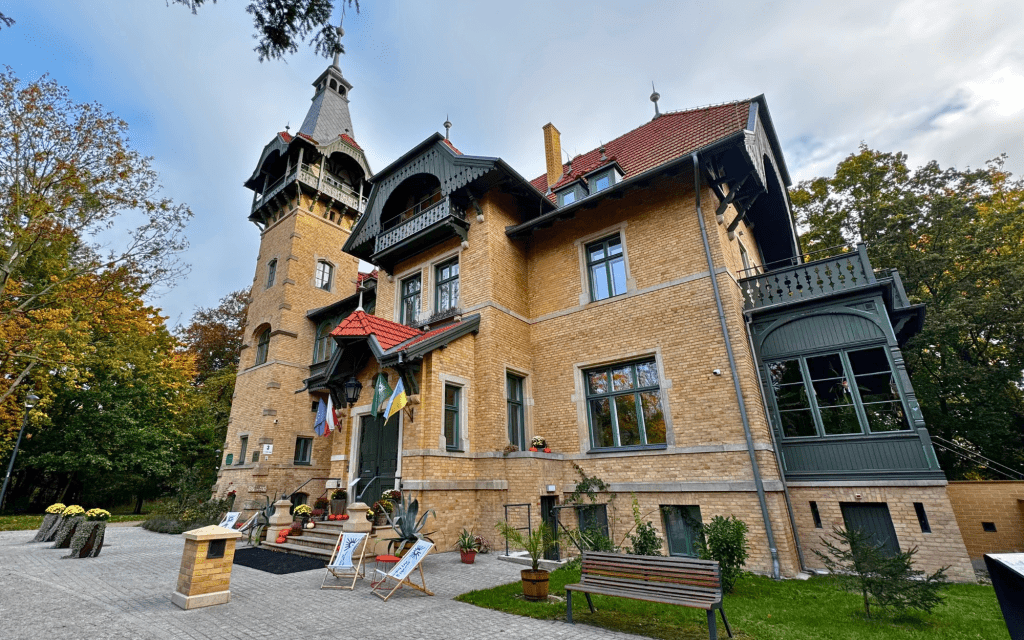

There are buildings that simply house history, and then there are buildings where history seems to seep through every brick, every floorboard, every shadow. Goyki 3 Art Inkubator in Sopot belongs firmly in the latter category. As I stand in the vaulted basement of this magnificent 19th-century villa with Kamil Antoniuk, my guide for the morning, I’m about to hear a story so tragic, so filled with mystery and unanswered questions, that it feels more like a Gothic novel than reality.

“The history of this family is very tragic,” Kamil warns me as we descend into the depths beneath the park. “Unfortunately, yes. There are so many strange situations.”

He’s not exaggerating.

A Wine Merchant’s Dream

The villa’s story begins in 1875 with Julius Friedrich Yü, the richest man in the area and owner of wine storehouses in Sopot, Berlin, and Wrocław. “He dreamed of having a residence in Sopot,” Kamil explains as we examine a detailed family tree displayed on the basement wall. “He had two apartments in Gdańsk, and he built this villa as a residence for three people: his wife Amanda Agnes, their adopted daughter Elza, and—according to his will—his grandchild.”

The basement where we’re standing was ingeniously designed. “It was built with double walls,” Kamil tells me. “Between the walls was a space, and in the past they put ice here, from the pond or from the Baltic. They could keep fresh meat here, and they also had a large private collection of wines. The double walls helped to insulate the space and maintain a good temperature.”

The family purchased the land in 1875 and immediately began creating a two-hectare park, collecting exotic trees. In 1877, they started building the house itself. “At the beginning, they built just a simple house with one floor,” Kamil explains. “But in 1894, Mr. Kaho, the chief architect of Gdańsk, designed the house. They built the residence following his plans until 1903.”

It took them nine years to complete their dream home. But Julius Friedrich never saw it finished. “Unfortunately, the owner died a few years before it was completed,” Kamil says quietly. “He was only 55—my age now. He was sick and went to Berlin for medical treatment. During treatment, he died. He was buried in Sopot cemetery.”

The Classen Connection

Julius Friedrich was more than just a wealthy wine merchant. “He also worked for the city of Gdańsk,” Kamil tells me. “And he was a philanthropist. He had a big heart. He helped many poor people. He shared his money, and he also loved collecting art and antiques.”

His wife Agnes had an intriguing surname: Classen. “It’s a very popular surname in Sopot,” Kamil notes. “You’ll probably see the Museum of Sopot, the beautiful villa next to the sea. That villa was built by Ernest Classen, who was famous here. We’ve been looking for a connection between Agnes and the famous Classen family from the museum, but we haven’t found any documents. So we don’t know if she’s from that family or not. But maybe, probably yes.”

After Julius Friedrich’s death, Agnes and their daughter Elza lived in the villa together. Elza eventually married Carl Körner from Wiesbaden, Germany. “He did exactly the same thing as Friedrich did,” Kamil says. “He owned wine storehouses. They married and lived in Wiesbaden. They had two sons: Hans and Herbert.”

A Murder-Suicide That Shocked Sopot

What happens next is almost too horrible to believe. In 1905, when Elza decided to divorce Carl, he refused to accept her decision. “He said he didn’t agree with her decision,” Kamil recounts. “And on February 8th, 1905, he did a horrible thing. He said he just wanted to spend time with one of their sons, Hans, who was five years old. He wanted to play games, spend time like father and son, in a lawyer’s office.”

Kamil pauses, and I can see the weight of what he’s about to tell me.

“They spent about an hour and a half together. But afterwards, he killed his son. He shot him. Then he opened the door—Elza was waiting for her son in the second room—and he committed suicide. It was terrible.”

The tragedy didn’t end there. “Two years after this awful event, Elza married again, to Max von Galen, a German baron. They had a son together. But in 1907, she died. She was only 25 years old.”

I’m stunned. “What a tragic life,” I manage to say.

“So much tragedy in her life,” Kamil agrees. “She saw everything, you know?”

The Grandchild’s Inheritance

After Elza’s death, her surviving son Hans lived in the villa with his grandmother Agnes. When Agnes died in 1928, Hans became the owner. “It’s very interesting because Friedrich’s will stated that he wanted to give this place to his grandchild,” Kamil explains. “Not to his wife or daughter, only to the grandchild. So Hans was the only one who inherited this place.”

Hans married Elza Schlager-Bertling, and they lived in the villa together. “We didn’t find any evidence that they had children,” Kamil says. “We think they didn’t have kids.”

For a while, it seemed the family’s tragic history might finally be over. But in 1940, at noon on an ordinary day, Hans died in the villa. He was only 38 years old.

“We have the document about his death,” Kamil tells me. “There’s information that he died from a gunshot. But there’s no information about whether it was suicide, an accident, or something else. It just says he died from gunshot wounds. But everybody in Sopot said he committed suicide.”

The Nazi Connection and a Disappearance

Hans’s wife Elza lived alone in the villa for two years after his death. Then, in 1942, she sold the building to the Nazi party—the NSDAP. “People said she sold it,” Kamil notes. “But she may have been forced to. In any case, she disappeared, maybe during the Second World War or after. People didn’t know what happened to this lady. She just vanished.”

After the war, the city of Sopot became the owner of the villa. But Kamil and his colleagues at Goyki 3 were curious about what really happened to Elza. “We started looking in archives in Germany and Poland, and we used American websites like ancestry.com, which is very helpful for finding information.”

What they discovered was extraordinary.

Unravelling the Mystery

“First, we found death announcements in newspapers,” Kamil explains. “The Museum of Sopot gave us some information. There was an announcement from Elza about Hans’s death. She wrote that ‘my husband died after a long period of suffering, and finally he found rest.’ But what about this long period of suffering if he died from a gunshot? So we thought maybe he was sick, or maybe he had mental problems.”

They found another clue in the death announcement of Elza’s father, who had been a senator in the Nazi party. “When he died in the sixties, the death certificate listed his daughters as still alive. And we found that Elza was still alive in the sixties, living in the city of Konstanz in Germany. It was a big surprise for us.”

Then they discovered documents from 1968 to 1970 about German laws allowing people to reclaim property lost during the war. “Elza was still alive, living in Baden-Baden,” Kamil reveals. “She said, ‘I want justice.’ She claimed that her husband had mental problems and was in a sanatorium in Poland. A doctor who was taking care of Hans called his boss at his workplace and said Hans was sick. When the boss heard about this, he may have told Hans he couldn’t work anymore. After that, Hans committed suicide.”

Elza also claimed she didn’t sell the building to the NSDAP. “She said Hans signed documents stating that his will was to give this place to the Nazi party,” Kamil continues. “But she said he was a sick man with mental problems, so he didn’t know what he was doing. She said the NSDAP came very quickly and took the beautiful antiques from here, and nobody helped her fight against them.”

The irony wasn’t lost on the investigators. “It’s very interesting because her father was a senator of the NSDAP,” Kamil points out. “So it’s strange that nobody helped her.”

The German government told her that if her husband had signed the documents, they couldn’t do anything. “They said, ‘Please stop trying.’ She said she understood, and then she disappeared again. She was in her seventies, living in Baden-Baden, and we don’t know what happened to her after that. When she died, nothing. No information about her. The second time in history she vanished.”

Unanswered Questions

As we stand looking at the family tree, I’m struck by the layers of tragedy. “Agnes outlived her husband, both of her children, and one of her grandchildren,” I observe. “That’s just incredibly tragic.”

“And who knows,” Kamil muses, “maybe it could have been a little bit different. Maybe someone from the NSDAP came to Hans and said, ‘You have to sign this document,’ and they could have killed him too, saying he committed suicide. We don’t know exactly, but there’s so much mystery. So many intriguing secrets about the family.”

From Private Villa to Public Space

The villa’s more recent history is less dark but no less interesting. In 1945, the city of Sopot took ownership. “Initially it was a 24-hour weekly kindergarten,” Kamil explains. “Kids lived here from Monday to Saturday and only went home on Sundays. But in 1957, they changed the function and created eight apartments for municipal workers. In total, 11 families lived here. Very nice people—we have contact with them. One of the men who lived here visited us today, actually.”

One notable resident was Jan Peszka, a Polish book writer. “He lived here and wrote a lot of books,” Kamil tells me. “In 1974, he wrote ‘The House with a Tower,’ a book about this building and the kids who lived here. His son, Juliusz Machulski, is a very popular film producer. It’s a famous family.”

The last residents moved out in 2013, and the building needed serious renovation. “The building and the park needed to be renovated because after the war, there hadn’t been any major renovation,” Kamil explains. “In 2019, the renovation process started. It took three years, with 90% of the money from the EU and the rest from the city of Sopot.”

A New Life as an Art Incubator

In 2019, Goyki 3 Art Inkubator was established, and in 2021, it moved into the renovated villa. “We’re an institute run by the city of Sopot,” Kamil explains. “We support artists, especially the creative process. We organise residency projects. We have studios—special rooms where artists can work for free. We organise art exhibitions and workshops on different subjects, not only art workshops but also ecology, because we have this beautiful park.”

The events they host are wonderfully varied. “We have concerts in our park during the summer. It’s called the Songwriter Festival,” Kamil says enthusiastically. “There are usually around 300 people in the park on garden chairs, enjoying beautiful music in a beautiful place. But sometimes we have smaller events. It’s very different.”

They also have a cinema room for documentary films and debates, and they host a silent disco in June for the opening of the season. “We have three DJs, and everybody can dance with headphones,” Kamil explains.

The park itself is now public, no longer private as it was in the Yü family’s time. “We have a social garden where we organise workshops about gardening—how to plant vegetables and herbs. We have bonfires and talk about planting flowers. We have meetings for people from Sopot and the Tri-City area.”

Connecting Past and Present

As we tour the villa, I’m struck by how carefully they’ve preserved its history whilst giving it new life. In the basement, there are photographs from the kindergarten era. On the ground floor, we find a sewing studio with machines and dress forms, and a screen-printing room with professional equipment.

The original features are stunning. Beautiful Delft-style tiles in what was once the kitchen. Gorgeous wood panelling in the living rooms. Original parquet flooring. A fireplace room with exposed wooden beams. And perhaps most remarkably, a baby grand piano that was discovered hidden inside a wall during the renovation.

“During the renovation in 2019, the workers found the piano,” Kamil tells me. “It had been disassembled, of course, and hidden in the wall. We think it was hidden during the Second World War by the German family. When they demolished the wall, they found it inside. It was renovated this year.”

The piano now sits in a beautiful reading room filled with books on diverse subjects. “Everybody can come here and just sit and read,” Kamil says. “We organise a very important festival called ‘Sopot by the Book’ every year. Each year we focus on a different country, different subjects. Next year it’ll be about Portuguese literature. This year it was about Romanian literature.”

A View from the Tower

Our tour culminates in a climb up the villa’s distinctive tower, the highest private tower in Sopot. “There was a special law in Sopot,” Kamil explains as we ascend. “If you wanted to build a tower on your house, you paid reduced taxes—you had a discount. They incentivised people to build towers because it was a symbol of the architecture. They wanted to retain the character of the place.”

From the top, the view is spectacular, even though the autumn leaves now obscure the Baltic Sea that Julius Friedrich paid to ensure he could see from every window. “He secured special permission so he could see the Baltic from all windows, from all floors, and nobody could block the view,” Kamil tells me. “He paid to see the Baltic all the time. That’s why he wanted it on the hill.”

The tower itself was damaged by fire in 1945, possibly destroyed by the Russian army. “During the renovation in 2019, they reconstructed the very top of the tower according to old pictures and old plans,” Kamil says. “So the tower looks like it used to before the war.”

Preserving Memory

What’s most impressive about Goyki 3 is how seriously they take the villa’s history. “We love the place very much, so we also love the history,” Kamil says. “We’re still connected with the history. We’re looking in archives all the time. We find new information constantly. Our director, Jacek Nasuła, made a film about the history. We document everything because the history is very important to us. We talk about the original family all the time. We have guided tours, so we present the building all year round, and people can come here and see the building whilst we talk about the history. We connect everything—new times and the history.”

They’ve even created a documentary film about the family, available on their YouTube channel with English subtitles, called “The Family.”

As I prepare to leave, taking one last look at the villa from the park, I’m struck by how this building embodies so much of what makes Sopot special. It’s a place where history isn’t just preserved—it’s actively investigated, questioned, and shared. Where tragedy and mystery coexist with creativity and community. Where a wine merchant’s dream, stained by unimaginable loss, has been transformed into a space where artists create, audiences gather, and the past speaks to the present.

“The history is very important for us,” Kamil had said. Standing here in the autumn sunshine, surrounded by the exotic trees that Julius Friedrich planted 150 years ago, I understand why. Some stories demand to be remembered, no matter how dark. And some buildings, like this one, refuse to let their secrets die.

Goyki 3 Art Inkubator

3 Jakuba Goyki Street

81-715 Sopot, Poland

goyki3.pl/en

Fast Facts:

Guided Tours: Available year-round (approximately 45 minutes)

- The Villa: Built 1877-1903

- Architect: Mr. Kaho, Chief Architect of Gdańsk

- 2-hectare park with exotic trees

- Highest private tower in Sopot

- Renovated 2019-2021 (90% EU funding)

Current Functions:

- Artist residencies and studios

- Art exhibitions

- Cinema/documentary screenings

- Workshops (art, ecology, gardening)

- Concerts and festivals

- Reading room and library

- Screen-printing facilities

- Sewing studio

Notable Events:

- Songwriter Festival (summer concerts in the park)

- “Sopot by the Book” literary festival

- Silent disco (June season opening)

- Year-round cultural programming